- Home

- Léonie Kelsall

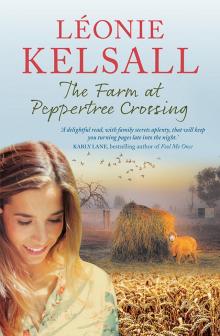

The Farm at Peppertree Crossing

The Farm at Peppertree Crossing Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

First published in 2020

Copyright © Léonie C. Kelsall 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76087 780 4

eISBN 978 1 76087 456 8

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Nada Backovic

Photos: Gary Beresford (‘First Light’); iStock (wheat); Getty Images (woman)

For Taylor,

Who knows what she wants

And will get it.

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Roni closed her fist around her keys. The longest metal shaft protruded between her fingers, a perfectly legal weapon. She’d sensed the presence behind her about five blocks from the train station, where the streetlights were spaced farther apart. It paused when she paused. Hurried when she hurried. And disappeared into the shadows when she turned.

Most women were smart enough to travel in pairs around here.

But most women didn’t have to work late in the city on a Wednesday night and then hike two klicks home from the train station.

The guy who dogged her footsteps was an idiot; any woman who risked walking this neighbourhood at night was no stranger to his type. Roni dug bitten nails into the key as it slipped between her fingers. Tightened her hand on the cracked leather strap slung across her chest. The self-defence instructor had insisted bags should only ever be carried on one shoulder, and surrendered instantly on demand. Better a handbag than your life, he’d said, handing out printed memes.

Whoever spent their Sunday coming up with that little gem had far more disposable income than Roni did. No way was anyone getting her bag without producing a knife.

She broke into a jog as the back of her apartment block came into view, the few unbroken streetlights along the cracked pavement flickering beacons in the gloom.

A chill gust slammed the smeared glass of the rear entry door behind her. Dead leaves and empty chip packets scuttled inside to join the damp mound against the wall of letterboxes. She pinched her nose at the dank smell; once spring arrived properly, the rubbish would still blow in, but at least the mould would retreat. One eye on the external door, she keyed open her box.

Eight lung-cramping flights of stairs separated her from the further safety of her fourth-floor apartment. Each landing had once boasted a window, a deception to make the structure seem less prison-like. Now, urban art decorated the boarded-up holes.

She paused on the third landing, holding her breath as she made certain there were no sounds of pursuit from below. Her racing heart slowed a notch, and she took a second to compose herself before she hammered on door three-four-seven. Footsteps thundered from above, then a couple of kids pushed past, leaping down steps three at a time. Beyond the door she could make out Mr Edwards’ familiar shuffle, his ever-present carpet slippers sliding on the gritty tiles. She dug into her bag, pulling out the prescription she’d had filled for him.

‘Come in, Roni, come on in.’ Lonely pleading was evident, as always, in Mr Edwards’ tone as he tugged open the door and held out arthritic claws for the package. And, as always, she shook her head. It was one thing to run minor errands for her long-term neighbours but quite another to enter their homes, their lives.

‘Let me get my wallet, then,’ Mr Edwards mumbled, rubbing at the patchy grey stubble on his liver-spotted cheeks. He turned to make the laborious trip back across his tiny apartment.

‘No rush. You can fix me up tomorrow.’ This time she would have to make sure she accepted the money, though. Not that she’d ever had money to burn, but now she was definitely not in a position to hand out charity.

Over Mr Edwards’ shoulder she saw a can of baked beans perched on the tray table alongside his tattered recliner, a fork dribbling orange slime onto the plastic surface. She grimaced. Mr Edwards’ scripts didn’t cost her much—he was on the PBS—and if he insisted she take the money tomorrow, she would use it to pick him up a loaf of sliced white to go with his beans.

She backed away, waving a farewell, then gripped the handrail to haul herself up the final flights. Groaned as chewing gum sucked onto her fingers. As Rafe loved to say, no good deed went unpunished. After more than a dozen years, she could just about hear her boss’s voice in her head.

Her door was one of many identical rectangles in the beige corridor of dozens of apartments, but it at least had an operating lock. The barrel rattled as she keyed it and shoved open the door, reaching for the light switch.

Lips pursed, she squeaked through her teeth. ‘Scritches?’ she called, again making the high-pitched squeak he always responded to. Her nose wrinkled at the ammonia waft. There was a reason pets weren’t permitted in the block, but Scritches had been with her eight years—ironically, from the week of her twenty-first birthday, as though he’d been some sort of cosmic gift. The only gift she’d received that year—or any other. Roni would resort to living under newspaper on a park bench before she would part with him. Greg had found that out last weekend. For years he had been keen for her to move in with him and split the rent. With her lease ending, it seemed the timing was right, despite her reluctance to give up the smallest fraction of her independence.

But then Greg had made it clear that Scritches wasn’t welcome.

And she had made it clear that she was through with Greg.

He hadn’t been worth fighting for. Not much in her life was.

She hadn’t even been truly disappointed in him. Because disappointment would mean she’d had expectations—and she’d learned long ago n

ever to allow that to happen.

The cat responded to her call, instantly underfoot and rubbing against her calves. Then he hooked his claws into her jeans to stretch to his full, impressive height against her thigh.

‘Hey, you daft thing. How’s life in the castle?’ Certainly better than it had been years back, when she’d found him cowering behind a dumpster at the back of the apartment block. Each time the local kids approached, the scruffy kitten had erupted into belly-rumbling purrs, thrusting his broad nose into their outstretched hands. Then bemused hurt would take over his expression as they pelted him with rocks and yanked his tail.

Roni had chased the kids off and left the kitten to fend for itself.

She had done the same the next day, pretending not to see the graze across his pink nose where a pebble had found its mark. Pitiful mewing followed her footsteps as she headed for the train, but she had hardened her heart.

The next day, repeating the intervention, she had refused to wonder how long the kitten would search for love from those who abused it. Or how it would escape the arctic wind that cut through the littered, empty carpark.

On the fourth day she had shoved the scrawny, wet bundle of malnourished fluff under her coat, where he had immediately set to kneading her with tiny, sharp claws, his purr vibrating through both of them. Against her chest he had felt so … alive. So trusting and willing to give affection, without expectation or demand.

She had been wrong on that score; it turned out Scritches was a demanding little ass.

He wove through her legs now as she made for the bathroom. ‘Okay, I get it. Priorities.’ She slid down the door jamb, feet shoved against the base of the bed, and clicked her fingers. The cat bounded heavily into her lap, butting her chin so hard her teeth knocked together. As she scratched the base of his spine he arched ecstatically, and Roni tugged on the ragged ear that lent him the appearance of a street brawler. ‘We’re both fakes, aren’t we?’ Sure, she’d talked tough to herself on that walk home, been prepared to face off with a potential attacker for the second time this year, but that didn’t mean her heart wasn’t still thumping hard enough to make her feel sick.

God, she hoped that was why she felt sick.

Because apparently the cat wasn’t the only thing Greg wouldn’t tolerate in his life. After half a decade together—years where she’d pretended to herself that maybe what she’d found was love, not just someone to provide the safety that seemed to come with familiarity—she thought she knew Greg. As much as either of them, both products of the foster system, chose to let anyone know them. But she’d been broadsided by his boast last week that he’d been skipping out on paying child support, denying responsibility for at least two kids somewhere in Sydney.

Two more children who didn’t know their father.

Although, maybe they were better off without him. Was it worse to know the parents who hadn’t wanted you, or to always wonder who your family was and why they hadn’t loved you enough to keep you? She shook her head as she hauled herself up and retrieved her handbag. That wasn’t something she’d ever have an answer to, so there was no point letting her mind wander that way. She tossed the mail she’d collected from her defaced letterbox onto her bed and grimaced as she took out the chemist’s package. The grease from the patchily translucent paper bag crammed alongside it slicked her fingertips. ‘You’re in luck, Scritch. Beef steak.’

Stepping over the instantly ravenous cat, she put the chemist’s parcel on the cracked pink laminate vanity, then shoved aside the curtain across the shower alcove. As usual, Scritches’ bowl was empty. Juvenile abandonment haunting him, he would always wolf down whatever food she offered. She split open the pies and dumped the gelatinous mass into the bowl. ‘Nope, no pastry.’ She fended off his sneak attack with her foot. ‘Rafe gave us this lot free, so they’re not exactly fresh.’

As she rinsed her hands, water splashed the chemist’s bag. Her gut clenched. She shook her hands, as though the nervous tingle would disappear from her fingertips along with the droplets, and then she shoved the test into a drawer. Until she peed on that stick, the problem wasn’t real. Which meant she could assess the hypothetical alternatives of the hypothetical situation with hypothetical clinical detachment.

Abortion.

Adoption.

Acceptance.

Fingers wrapped around the drawer handle, she closed her eyes, focused on tamping down the surge of despair. The thing was, although she pretended she had options, she knew the truth. If she was pregnant, it was her own fault. She was an adult, and she hadn’t been forced, cajoled or coerced. Not this time. So there was no way she would allow the child to be torn from the one place that should provide unquestionable safety.

Adoption? Supposedly vastly different to the foster system she’d grown up in—she would never consign any kid to a repeat of her life—but still she was wary without an iron-clad guarantee.

So, that left door number three. If she’d screwed up, she would have to keep the baby. Not only that but she would have to find a way to provide for it, because any hope of help from Greg was out of the question.

Scritches jumped as she slammed the drawer.

Leaving the bathroom door partly open, she took the six steps through the bedroom, pausing to scoop up the mail she’d tossed on the bed, and into the kitchen. She pulled a stool from beneath the bench that served as food prep area, desk and the cat’s bed when he could get away with it. His favourite spot, though, was the window ledge. For almost a decade, his experience of the outside world had been in shades of grey, filtered by grime-covered glass. Plastered against her window like a furry starfish, perhaps he occasionally caught sight of his family skulking around down there and realised how much better off he was without them.

She and Scritches only needed each other.

Roni perched on the stool and flicked through the stack of mail, frowning at the fifth item. Her thumb rubbed the thick parchment, unease worming through her stomach. Nothing good ever came in a window-faced envelope. Especially not one embossed Prescott & Knight, Solicitors. What could a solicitor want with her? She’d done nothing wrong.

She ripped the envelope open.

Dear Ms Gates,

We act on behalf of Ms Marian Nelson. We have tried, unsuccessfully, to contact you via telephone regarding a personal financial matter. We would be pleased if you could call during business hours on the number listed above.

Sincerely,

Derek Prescott

She snorted. Either a luckless investment adviser who could tell her what to do with her whole twelve-hundred dollars of savings, or a scammer so basic they still used snail mail. At least it explained the unknown-number calls she’d recently ignored.

The fridge gave a geriatric wheeze and she lurched from the stool, her gaze flying to the door. Deadlocked, as always, the second she stepped inside.

But that didn’t mean the street-creep hadn’t followed her, wasn’t waiting in the stairwell. Or on the street.

She shoved the mail back into her bag, jerking the zip across as though she could contain her fear within the leather prison.

Hell, didn’t she have a right to feel safe in her own space?

Not that rights had ever counted for much in her life.

Chapter Two

She liked seeing the same faces each day. After more than ten years, the nameless people were family. She had invented their stories without needing to leave the security of her mental solitude, had kept them safely at arm’s length while enjoying the feeling of security that came with their familiarity.

The arrival of each train and ferry at Circular Quay saw a fresh crowd engulf the takeaway shop. First in were the tradies in orange or yellow hi-vis vests and white hardhats, breakfasting on bacon-and-egg rolls washed down with cartons of iced coffee as they headed toward the city building sites. Most days, Roni would cop the same chat-up line. Hey, sweetheart, how about you come hang at the pub this arvo?

And every time she

would silently refuse, sparing them only a tight smile.

At 6.17 the pinstriped businessman would appear, his shoes reflecting the fluoro overheads. After four years, she had forced herself to allow their hands to touch as she shoved his latte across the counter, inhaling a caffeine-eclipsing jolt of expensive aftershave, and he shoved five bucks, never waiting for his change. Impeccably groomed and polite, the guy should be everything a woman would want.

But Roni only made the contact to prove to herself that she could, a daily reminder of how far she’d come from being the kid who’d flinched from Rafe’s gaze when she’d come in here begging for an after-school job. She had her shit together now, her memories under control.

Waves of office workers, schoolkids and then, finally, the unfamiliar faces of tourists, populated the rest of her day.

She rang up a sale on the till and raised her voice over the thunder of a train on the platform above them. ‘Rafe, I’m taking lunch, okay?’

‘Sure.’ Her boss glanced at the clock above the cake counter. Not yet ten-thirty, but he liked her to take her break before the rush. They’d fallen into a routine over the years since she graduated. At first she’d juggled two jobs, but once Rafe discovered she was working nights at a service station, he’d opened up a full-time position for her.

He paid poorly and worked her hard, but he was quick with a laugh and a sympathetic ear on the rare occasions she chose to share. She liked to tell herself he was what a dad would have been like.

‘Was the sun up when you got in?’ Rafe slid the cake cabinet door shut. ‘Heading for the gardens?’

‘Not today.’ She often spent lunch sprawled beneath the parrot-filled Moreton Bay figs in the Royal Botanic Garden. Other days, she would dangle her legs over the edge of the quay, admiring the rainbow petroleum slicks as ferries beetled past the white sails of the Opera House. She rummaged in her bag. ‘Scritch reckons crumbs aren’t a patch on fish-shaped biscuits, so I’ve got to shop.’

‘Crazy cat lady. Y’know that animal doesn’t actually have an opinion, right?’

The Farm at Peppertree Crossing

The Farm at Peppertree Crossing